We're not building The Matrix

03 Jul 2017I love a good tech structure discussion at work and there’s one that’s been rumbling on and off for years that prompted one of my colleagues to exclaim the phrase that became the title of this post – “We’re not building The Matrix”. The debate is about how much autonomy an object/entity/game object/component should be given and ultimately how to structure the logic of a program.

Autonomous Monty

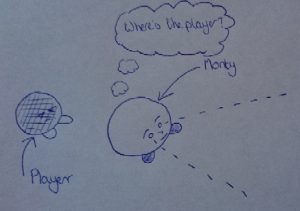

Firstly let me clarify what I mean by autonomy; the level of autonomy of an object is a measure of its ability to take decisions and to execute code based on those decisions. Let’s use the example of a simple 2 state enemy AI guard (called Monty). Monty has the following states and behaviour:

- If Monty cannot see the player he is patrolling.

- If he sees the player, he is attacking.

If Monty is designed autonomously he is responsible (by him I mean the code that comprises the entity “Monty”) for checking if he can see the player and for taking the appropriate action. Now it doesn’t matter if this behaviour is coded directly into the entity or whether the behaviour exists via components attached to the entity or any other way we wish to build Monty; ultimately Monty has been given the ability to make a decision (execute code) based on whether or not he can see the player. There is a certain allure with this type of design as it maps quite nicely to how people operate in the real world, however I believe (as did my colleague who made the Matrix reference) that building programs this way quickly leads to control flow issues, lack of flexibility and fragile codebases.

Through the Keyhole

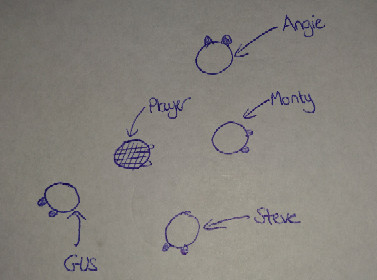

For the rest of this post let’s assume that Monty is a single MonoBehaviour attached to a Unity GameObject and that he has his own update loop (called by Unity when the GameObject is active) that runs his behaviour. The problem is that up until now we have been considering Monty almost in isolation (my colleague describes this rather brilliantly like “programming through a keyhole”)…

…but if we think about the bigger picture…

…Ok. So Monty has a bunch of mates who are also guards. This makes sense “where there’s one there’s many” right? Let’s add some complexity and see how our structure holds up:

Complexity modifier 1: The game designer slides over and tells you that the player can now become invisible and when invisible cannot be seen by “Monty” or any of his patrolling pals. You’re not worried, Monty can handle this:

Monty already has access to some of the player state right? At the very least the player position in order to decide whether he can see the player or not. We can just give Monty access to the data that states whether the player is invisible or not and use that to influence his decision – job done, ticket closed. However something rankles a bit because the player is invisible to all patrollers and yet all of them are now checking every update loop whether the player is invisible or not. Never mind it’s not that big of a deal.

Complexity modifier 2: The designer enters stage left and whispers in your ear that the player now has a flash-bang grenade that when deployed will disable guards and allow the player to be “invisible” to any guards in an unspecified radius for an unspecified time period. Hmm, a little more tricky:

Ok, so we subscribe Monty and his friends to an event that is triggered whenever the player uses a flash-bang. Monty can then check if he is within the unspecified radius and start a timer during which he will consider the player invisible. Seems pretty elegant.

Complexity modifier 3: The designer apparates behind you and declares that focus tests have found that the flash-bang is too powerful and has made the game too easy. It is being swapped out for a “McGuffin” which is a new weapon that will fire sleeping darts at the closest 2 guards – same result as the flash-bang, the player will be invisible to sleeping guards for a certain time period.

No problem, clickety-clack of the keyboard and Monty now knows about all his friends and their locations and they all know about him and they all listen to the event on the player and when the event is triggered they all calculate who is closest to the player and two of them come to the conclusion it is them and put themselves into the “sleep” state and start their timers, right?

Making Informed Decisions

Okay so that’s a bit of a contrived example and no-one would really design a system in that way surely? Let’s make it simpler, let’s pretend that Monty isn’t a hotshot, AI guard but instead a humble UI button (well he is a MonoBehaviour that exists on a UI object that has a button component and is hooked up to the button click event – but you get the gist). Monty has one job; when he is pressed he presents a pop-up to the user – simples. Monty is very good at his job, every time he is pressed he dutifully presents his pop-up. Doesn’t matter if another pop-up is already being shown, doesn’t matter if the player is mid-tutorial and Monty just happens to be on-screen, doesn’t matter that he might break the game flow. It’s not Monty’s fault, it’s not that he doesn’t care, it’s that he doesn’t know!

All jokey examples aside, that is why this kind of autonomous programming is bad. How many projects have you worked on where an object took some action that broke the program flow because the object did not first check the state of the program before modifying it in some way (a la the Monty button)? Or when game rules end up scattered throughout the codebase with everything having access to the state of everything else and coupling turned up to 11?

In order to make a correct (informed) decision the object making the decision must have access to all the information. In the weapon example that information is the location of the player and the location of all guards. In the UI example it is the awareness of the state of the application and whether it is in a tutorial or whether a pop-up is already displayed (and what the rules are – do we delay showing our pop-up, do we hide the existing one, do we appear over the top?). We can give the autonomous objects access to that information but these objects then become large complex beasts, full of state checks and decision flow logic that is really above their pay grade. Not to mention getting access to that data can be tricky (how does Monty get access to the locations of all the other guards?).

Programs are typically structured as hierarchies – think about the basic Unity structure:

But having a hierarchy alone is not enough unless the decisions are made from the top (even if you add a “GuardManager” to the above example, that creates and holds references to all guards, it doesn’t help the flow if the guards are still calling the shots). The hierarchy should not just represent ownership, it should also reflect the flow of code execution. Think about any corporate structure, you might make suggestions to your boss but the decision on what you should work on is his/hers to take because he/she has access to the bigger picture. This repeats all the way to the root of the hierarchy, decisions should be taken by those who have access to all the information, if you only have access to some of the information and still take a decision (like poor Monty) then that’s when issues arise.

Control from Top to Bottom

Autonomy is an illusion because looking back over the code you can clearly see the constraints placed on autonomous objects by the rules of the application (e.g. “Don’t attack the player if he is invisible”, “Don’t show a pop-up if one is already showing”). When structuring a program, information can flow in the direction from the leaves to the root (“I’ve spotted the player” or “I’ve been clicked”) but execution of state manipulating code should always come from the direction of the root to the leaves (“Attack the player”, “Go to sleep” or “Show/hide a pop-up”). Doing this makes it easier to implement more complex logic rules that operate on a set rather than a single object (e.g. only put 2 guards to sleep, make the guards split up to flank the player’s position, queue a new pop-up until the other one has been dismissed). If we restructured the guard example above to defer all decisions to the “GuardManager” then we have no trouble implementing the “McGuffin” weapon; as the manager can easily determine the closest 2 guards to the player and notify them to “go to sleep”.

I feel that Unity (and despite my protests ChilliSource) encourage this kind of autonomous structure by giving entities/game objects update loops tied to the scene rather than an owning system. If we want to stop updating all guards we have to disable them all rather than just not updating the GuardManager that in turn doesn’t update the guards. We are encouraged to think of entities like self-contained actors in the world rather than as data/state in a system. If we want to use composition to build complex behaviours we can and we should; but choosing when to execute those behaviours is not the domain of the entity. The guard entity is really nothing more than data – a position and a state, if we choose to add methods for manipulating that state (e.g. move to, go to sleep, attack, etc) into the guard entity for syntactic sugar then fine as along as those methods don’t affect any state other than the internal state of the guard. If the guard wishes to attack the player he may pass information up the chain stating that he has attacked (or rather wishes to attack) the player but it is not the guard’s responsibility to remove health from the player directly (what if the player has a shield? What if the player is invincible during the tutorial?). The alternative is to add even more state to the guard and to toggle that state based on the state of the program (e.g. the tutorial is active so Monty you are blind until told otherwise) and that leads to even more complex objects.

Some Rules

Here is the crux of the above distilled into rules that I try to follow when structuring a program:

-

A system (I’m using the term system as a catch-all for logic and state) should only directly manipulate its internal state (in our example the GuardManager is a system and the guards are its internal data). Never change core state when you can’t see the bigger picture and never bypass the team leader and ask his/her team to do something directly – that’s bad form (and the lead (e.g. GuardManager) may know of rules or have access to information that the boss doesn’t!).

-

If a system wishes to manipulate state external to it (i.e. show a pop-up, decrease the player’s health, etc.), then it must make a request up the tree to do so (remember information flow is bi-directional).

-

Code (especially when it manipulates core state) should be executed by systems that have all the information (as specified by the application rules). These systems deal with the requests that are passed up the tree to them.

And that’s it. By ensuring that the flow of the application goes from the root to the leaves we have made it easier to apply game rules, enable/disable entire branches of the program and to perform operations on groups of data. Hopefully we also reduce bugs caused by mismanagement of game state. Ultimately when programming we have full control of the flow, rules and data of our programs why would we want to mimic the real world and all its problems? Unless, of course, we were building The Matrix.